Mythology of Benjamin Banneker

According to accounts that began to appear during the 1960s or earlier, a substantial mythology has exaggerated the accomplishments of Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806), an African-American naturalist, mathematician, astronomer and almanac author who also worked as a surveyor and farmer.

Well-known speakers, writers, artists and others have created, repeated and embellished a large number of questionable reports during the two centuries that have elapsed since Banneker lived.[1] Several urban legends describe Banneker's alleged activities in the Washington, D.C., area around the time that he assisted Andrew Ellicott in the federal district boundary survey.[2][3][4] Others involve his clock, his astronomical works, his almanacs and his journals.[3][5] Although part of African-American culture, many of these accounts lack support by historical evidence. Some are contradicted by evidence.

A United States postage stamp and the names of a number of recreational and cultural facilities, schools, streets, and other facilities and institutions throughout the United States have commemorated Banneker's documented and mythical accomplishments since the two centuries he lived.

Washington, D.C.

Silvio Bedini (1981)

A number of undocumented stories connecting Benjamin Banneker with the planning and survey of the federal capital city have appeared over the years. During the late 1900s and early 2000s, historian Silvio Bedini wrote and performed research about Banneker that refuted some of these tales while working in Washington, D.C., for over 40 years at the Smithsonian Institution's Museum of History and Technology/National Museum of American History.[2][6]

In early 1791, Andrew Ellicott and his team, which initially included Banneker, began a survey of the boundaries of the future 100 square miles (259.0 km2) federal district. The district, which would contain the nation's capital, was to be located along the Potomac River (see Boundary Markers of the Original District of Columbia).

Soon afterwards, Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant began to independently prepare a plan for the smaller federal capital city (the City of Washington), to be located within the federal district on the Maryland side of the river in accordance with the 1790 federal Residence Act, as amended (see L'Enfant Plan).[7][8] In late February 1792, President George Washington dismissed L'Enfant, who had failed to have his plan published and was experiencing frequent conflicts with three commissioners that Washington had appointed to supervise the planning and survey of the federal district and city.[9][10]

In a 1969 publication, Bedini reported that Martha Ellicott Tyson, a Quaker abolitionist who was a daughter of George Ellicott (Andrew Ellicott's cousin)[11] and a co-founder of Swarthmore College,[12] had prepared an account about Banneker's alleged involvement with the survey and planning of the federal city within her papers, which her own daughter had edited after her death.[13] The Friends (Quakers) Book Association published the edited papers in Philadelphia during 1884.[13] Bedini noted that the association's publication stated:

Major Ellicott selected Benjamin Banneker as his assistant upon this occasion, and it was with his aid that the lines of the Federal Territory, as the District of Columbia was then called, were run.

It was the work, also of Major Ellicott, under the orders of General Washington, then President of the United States, to locate the sites of the Capitol, President's House, Treasury and other public buildings. In this, also, Banneker was his assistant.[13]

Bedini further noted that writers had repeated and embellished this account, sometimes in conflicting ways:

The name of Benjamin Banneker, the Afro-American self-taught mathematician and almanac-maker, occurs again and again in the several published accounts of the survey of Washington City [D.C.] begun in 1791, but with conflicting reports of the role which he played. Writers have implied a wide range of involvement, from the keeper of horses or supervisor of the woodcutters, to the full responsibility of not only the survey of the ten-mile square but the design of the city as well. None of these accounts has described the contribution which Banneker actually made.[14]

One version of the tale claims that Banneker "made astronomical calculations and implementations" that established points of significance within the city, including those of the White House, the Capitol, the Treasury Building and the "16th Street Meridian" (see White House meridian). Other versions state that Banneker assisted Andrew Ellicott in locating the sites of some or all of those features or "laid out Washington".[15]

Daniel A. P. Murray

Another Banneker story emerged in 1921 when Daniel A. P. Murray, an African American historian serving as an assistant librarian of the Library of Congress, read a paper before the Banneker Association of Washington that connected Banneker with L'Enfant's plan for the capital city.[16] The paper stated:

... L'Enfant made a demand that could not be accorded and ... in a fit of high dudgeon gathered all his plans and papers and unceremoniously left. ... Washington was in despair, since it involved a defeat of all of his cherished plans in regard to the "Federal City." This perturbation on his part was quickly ended, however, when it transpired that Banneker had daily for the purposes of calculation and practice, transcribed nearly all L'Enfant's field notes and through the assistance they afforded Mr. Andrew Ellicott, L'Enfant's assistant, Washington City was laid down very nearly on the original lines. ... By this act the brain of the Afro-American is indissolubly linked with the Capital and nation.[17]

In 1976, Jerome Klinkowitz stated within a book that described the works of Banneker and other early black American writers that Murray's report had initiated a myth about Banneker's career. Klinkowitz noted that Murray had not provided any support for his claim that Banneker had recalled L'Enfant's plan for Washington, D.C. Klinkowitz also described a number of other Banneker myths and subsequent works that had refuted them.[16]

When describing in 1929 the ceremonial presentation to Howard University in Washington, D.C., of a sundial memorializing Banneker, an African-American newspaper, The Chicago Defender, reported that a speaker had claimed that:

... he (Banneker) was appointed by President George Washington to aid Major L'Enfant, famed French architect, to plan the layout of the District of Columbia. L'Enfant died before the work was completed, which required Banneker to carry on in his stead.[18]

However, a 1916 book that won the 1917 Pulitzer Prize for History had earlier reported that L'Enfant died near the City of Washington in 1825, more than 30 years after he prepared his plan for the federal capital city.[19] The United States Congress acknowledged the work that L'Enfant had performed when preparing his plan for the capital city by voting to pay him for his efforts.[20]

A lobby in the Recorder of Deeds Building, which was constructed from 1940 to 1943 in Washington, D.C., displays a U.S. Treasury Department, Section of Fine Arts mural that features an imaginary portrait of Banneker as a young man. The mural also depicts an 1800 Plan of the City of Washington, William Thornton's design for the west view of the Capitol building and a model of the White House. A corner of the mural portrays Banneker and Andrew Ellicott showing to three men a map of the area between the "Potowmack River" and the Eastern Branch within which the City of Washington would later be planned.[21]

The oil portrait was the winner of a juried competition that the section held on behalf of Doctor William J. Thompkins, an African-American political figure who was at the time serving as the Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia. The competition announcement stated that seven mural subjects had been "carefully worked out by the Recorder...following intensive research" to "reflect a phase of the contribution of the Negro to the American nation." A mural on the subject of "Benjamin Banneker Surveys the District of Columbia" was to "show the presentation by Banneker and Mayor Ellicott, of the plans of the District of Columbia to the President, [and] Mr. Thomas Jefferson" in the presence of Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton.[22]

In 1949, an activist for African-American causes, Shirley Graham, authored a book about Banneker's life entitled Your Humble Servant. Graham's notes on her sources stated:

This story of Benjamin Banneker has been constructed within the framework of little known true facts. All dates and main events can be documented. All gaps have been filled in with incidents of whose probablity I am convinced.[23]

However, when describing Graham's book in a 1972 biography of Banneker, Silvio Bedini stated that her work had been written for young people, was highly fictionalized and, having become popular, had "resulted in yet more confusion concerning Banneker's achievements and their importance".[24]

Graham's account of Banneker's involvement in the origins of the District of Columbia stated that Banneker worked with L'Enfant during the planning and survey of the federal district. Her story told that in early 1792, L'Enfant "packed everything and departed – taking the plans with him." When Banneker learned of this, he took an adventurous trip to his home in Ellicott's Mills, Maryland. While at home, Banneker reconstructed L'Enfant's plan from memory within a three-day period. The redrawn plan provided the framework for the later development of the city of Washington.[23] A number of books, reports and websites have repeated or extended Graham's fable before and after Bedini wrote his 1972 critique of her book.[25]

Documents published in 2003 and 2005 supporting the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. (including a report that a presidential commission planning the museum sent to the president and the Congress), also connected Banneker with L'Enfant's plan of the city of Washington.[26] When the museum opened on the National Mall in September 2016, an exhibit entitled "The Founding of America" displayed a statue of Banneker holding a small telescope while standing in front of a plan of that city.[27]

News reports of the museum's opening stated that Banneker "was called on to help design Washington, D.C." and "is credited with helping map the layout of the nation's capital".[28] A National Park Service web page subsequently stated in 2017 that Banneker had "surveyed the city of Washington with Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant".[29]

Historical research has shown that none of these legends can be correct.[2][30][31] As Bedini reported in 1969, Ellicott's 1791 assignment was to produce a survey of a square, the length of whose sides would each be 10 miles (16.1 km) (a "ten mile square").[32] L'Enfant was to survey, design and lay out the national capital city within this square.[32][33]

Ellicott and L'Enfant each worked independently under the supervision of the three commissioners that President Washington had earlier appointed.[32] Bedini could not find any evidence that showed that Banneker had ever worked with or for L'Enfant.[30][32]

Julian P. Boyd, a professor of history at Princeton University, emphasized this in his 1974 review of information concerning the survey of the federal district and city in Bedini's 1972 book, stating:

First of all, because of unwarranted claims to the contrary, it must be pointed out that there is no evidence whatever that Banneker had anything to do with the survey of the Federal City ... All available testimony shows that he was present only during the few weeks early in 1791 when the rough preliminary survey of the ten mile square was made; that, after this was concluded and before the final survey was begun, he returned to his farm and his astronomical studies in April, accompanying Ellicott part way on his brief journey back to Philadelphia; and that thenceforth he had no connection with the mapping of the seat of government. ...

In any case, Banneker's participation in the surveying of the Federal District was unquestionably brief and his role uncertain.[2]

Banneker left the federal capital area and returned to his home near Ellicott's Mills in April 1791.[30][34][14] At that time, L'Enfant was still developing his plan for the federal city and had not yet been dismissed from his job.[30] L'Enfant presented his plans to President Washington in June and August 1791, two and four months after Banneker had left.[30][34][35][36]

There never was any need to reconstruct L'Enfant's plan. After completing the initial phases of the district boundary survey, Andrew Ellicott began to survey the future federal city's site to help L'Enfant develop the city's plan.[37] During a contentious period in February 1792, Ellicott informed the commissioners that L'Enfant had refused to give him an original plan that L'Enfant possessed at the time.[38]

Ellicott wrote in his letters that, although he was refused the original plan, he was familiar with L'Enfant's system and had many notes of the surveys that he had made himself.[40] Additionally, L'Enfant had earlier given to Washington at least two versions of his plan, one of which Washington had sent to Congress in December 1791.[35][41]

The U.S. Library of Congress holds in its collections a manuscript of one such plan for the federal city. The plan identifies "Peter Charles L'Enfant" as its author.[42]

Andrew Ellicott, with the aid of his brother, Benjamin Ellicott, then revised L'Enfant's plan, despite L'Enfant's protests.[38][44][45][46] Shortly thereafter, Washington dismissed L'Enfant.[38][44][45]

After L'Enfant departed, the commissioners assigned to Ellicott the dual responsibility for continuing L'Enfant's work on the design of the city and the layout of public buildings, streets, and property lots, in addition to completing the boundary survey.[30][32] Andrew Ellicott therefore continued the city survey in accordance with the revised plan that he and his brother had prepared.[9][38][45][47][48]

There is no historical evidence that shows that Banneker was involved in any of this.[2][44] Six months before Ellicott revised L'Enfant's plan, Banneker sent a letter to Thomas Jefferson from "Maryland, Baltimore County, near Ellicotts Lower Mills" that he dated as "Augt. 19th: 1791", in which he described the time that he had earlier spent "at the Federal Territory by the request of Mr. Andrew Ellicott".[49]

As a researcher has reported, the letter that Ellicott addressed to the commissioners in February 1792 describing his revision of L'Enfant's plan did not mention Banneker's name.[50] Jefferson did not describe any connection between Banneker and the plan for the federal city when relating his knowledge of Banneker's works in a letter that he sent to Joel Barlow in 1809, three years after Banneker's death.[51]

In November 1971, the U.S. National Park Service held a public ceremony to dedicate and name Benjamin Banneker Park on L'Enfant Promenade in Washington, D.C.[52][53] The U.S. Department of the Interior authorized the naming as an official commemorative designation celebrating Banneker's role in the survey and design of the nation's capital.[53]

Austin H. Kiplinger (1981)

Speakers at the event hailed Banneker for his contributions to the plan of the capital city after L'Enfant's dismissal, claiming that Banneker had saved the plan by reconstructing it from memory.[52] Bedini later pointed out in a 1999 biography of Banneker that these statements were erroneous.[52]

During a 1997 ceremony that again commemorated Banneker while rededicating the park, speakers stated that Banneker had surveyed the original City of Washington.[54] However, research reported more than two decades earlier had found that such statements lacked supporting evidence and appeared to be incorrect.[2]

In 2000, Austin H. Kiplinger and Walter E. Washington, the co-chairmen of the Leadership Committee for the planned City Museum of Washington, D.C., wrote in the Washington Post that the museum would remind visitors about how Banneker had brought his mathematical expertise to complete L'Enfant's project to map the city.[55] A letter to the editor of the Post entitled District History Lesson then responded to this statement by noting that Andrew Ellicott was the person who revised L'Enfant's plan and who completed the capital city's mapping, and that Banneker had played no part in this.[56]

Appointment to planning commission for Washington, D.C.

Henry E. Baker

In 1918, Henry E. Baker, an African American serving as an assistant examiner in the United States Patent Office, wrote a biography of Banneker in The Journal of Negro History (now titled The Journal of African American History), which Carter Woodson edited. Baker's biography stated: "It is on record that it was on the suggestion of his friend, Major Andrew Ellicott, ..., that Thomas Jefferson nominated Banneker and Washington appointed him a member of the commission" whose duties were to "define the boundary line and lay out the streets of the Federal Territory, later called the District of Columbia".[57]

Baker also stated that Andrew Ellicott and L'Enfant were members of this commission. However, Baker did not identify the records on which he based his statements.[57]

In 1947, John Hope Franklin wrote in the first edition of his book From Slavery to Freedom: A History of American Negroes that the "most distinguished honor that Banneker received was his appointment to serve with the commission to define the boundary line and lay out the streets of the District of Columbia." Franklin also stated that Banneker's "friend", George Ellicott (Andrew Ellicott's cousin), was a member of the commission.[58]

In 1966, a book that Franklin co-authored made a similar statement, claiming that L'Enfant, Banneker and George Ellicott were the survey's commissioners.[59] Bedini subsequently wrote in a 1972 biography of Banneker that the claim was incorrect.[60]

Nevertheless, Franklin repeated in a 2000 edition of his book (whose title had become From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans) the statements that he had made in the book's first edition. The 2000 edition also stated that Thomas Jefferson had submitted Banneker's name to President Washington. The edition cited Baker's 1918 biography as the source of this information.[61]

Franklin's books did not cite any documentation to support their contention that George Ellicott participated in the planning and design of the nation's capital. Andrew (not George) Ellicott led the survey that defined the district's boundary lines and, with L'Enfant, laid out the capital city's streets. There is no historical evidence that shows that President Washington participated in the process that resulted in Banneker's appointment as an assistant to Andrew Ellicott on the district boundary survey team.[11]

A 1988 children's book entitled Book of Black Heroes from A to Z stated: "Banneker was the first black person to receive a presidential appointment. George Washington appointed him to the commission that laid out the city of Washington, D.C."[62]

In 2005, actor James Avery narrated a DVD entitled A History of Black Achievement in America. A quiz based on a section of the DVD entitled "Emergence of the Black Hero" asked:

Benjamin Banneker was a member of the planning commission for ____________ .

a. New York City

b. Philadelphia

c. Washington, D.C.

d. Atlanta[63]

Historical evidence contradicts the statements that Baker, Franklin and the children's book made and suggests that the question in the quiz has no correct answer. In 1791, President Washington appointed Thomas Johnson, Daniel Carroll and David Stuart to be the three commissioners who, in accordance with the authority that the federal Residence Act of 1790 had granted to the president, would oversee the survey of the federal district, and "according to such Plans, as the President shall approve", provide public buildings to accommodate the federal government in 1800.[64][65][66]

The Residence Act did not authorize the president to appoint any more than three commissioners that could serve at the same time.[67] Banneker, Andrew Ellicott, and L'Enfant performed their tasks during the time that Johnson, Carroll and Stuart were serving as commissioners. President Washington therefore could not have legally appointed either Banneker, Ellicott or L'Enfant to serve as members of the "commission" that Baker and Franklin described.

In 1972 and 1999, Bedini reported that an exhaustive survey of U.S. government repositories, including the Public Buildings and Grounds files in the National Archives and collections in the Library of Congress, had failed to identify Banneker's name on any contemporary documents or records relating to the selection, planning and survey of the City of Washington. Bedini also noted that none of L'Enfant's survey papers that he had found had contained Banneker's name.[30][68]

Bedini further stated that a writer had erroneously claimed in 1967 that Banneker had been appointed to the commission for the federal district's survey in response to a suggestion that Jefferson had made to George Washington.[30][68] Another researcher has been unable to find any documentation that shows that Washington and Banneker ever met.[69]

Boundary markers of the District of Columbia

During 1791 and 1792, Andrew Ellicott's survey team placed forty mile marker stones along the 10 miles (16.1 km)-long sides of a square that would form the boundaries of the future District of Columbia. The survey began at the square's south corner at Jones Point in Alexandria, Virginia (see Boundary markers of the original District of Columbia).[70][71] Several accounts of the marker stones incorrectly attribute their placement to Banneker.

In 1994, historians preparing a National Register of Historic Places registration form for the L'Enfant plan of the City of Washington wrote that forty boundary stones laid at one-mile intervals had established the district's boundaries based on Banneker's celestial calculations.[72] In 2005, a data gathering report for the planned Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C., stated that Banneker had assisted Andrew Ellicott in laying out the forty boundary marker stones.[73] Both the 2005 data gathering report and a 2007 historic preservation report for the NMAAHC repeated the statement that the boundary stones' locations had been based on Banneker's "celestial calculations".[74]

In 2012, Penny Carr, a regent of the Falls Church, Virginia, chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) wrote in an online community newspaper that Andrew Ellicott and Banneker had in 1791 put in place the westernmost boundary marker stone of the original D.C. boundary. Carr stated that the marker now sits on the boundary line of Falls Church City, Fairfax County, and Arlington County.[75] Carr did not provide the source of this information.

A 2014 book entitled "A History Lover's Guide to Washington" stated that both Ellicott and Banneker had "carefully placed the forty original boundary stones along the Washington, D.C. borders with Virginia and Maryland in 1791–1792".[76] Similarly, on May 8, 2015, a Washington Post article describing a rededication ceremony for one of the marker stones reported that Sharon K. Thorne-Sulima, a regent of a chapter of the District of Columbia DAR, had said:

These stones are our nation's oldest national landmarks that were placed by Andrew Ellicott and Benjamin Banneker. They officially laid the seat of government of our new nation.[77]

On May 30, 2015, a web version of a follow-up article in the Post carried the headline "Stones laid by Benjamin Banneker in the 1790s are still standing".[78] Disputing the headline's information, a June 1, 2015, comment following the article stated while citing an extensively referenced source[79] that Banneker had, "according to legend", made the astronomical observations and calculations needed to establish the location of the south corner of the district's square, but had not participated in any later parts of the square's survey.[80]

One of the references in the source that the comment in the Post cited was a 1969 publication that Silvio Bedini had authored. In that publication, Bedini stated that Banneker apparently left the federal capital area and returned to his home at Ellicott's Mills in late April 1791, shortly after the south cornerstone (the first boundary marker stone) was set in place during an April 15, 1791, ceremony.[14] In 1794, a permanent south cornerstone reportedly replaced the stone that was set in place during the 1791 ceremony.[81]

Citing a statement that Bedini had made in a biography of Banneker published in 1972,[82] historian Julian P. Boyd pointed out in a 1974 publication that there was no evidence that Banneker had anything to do with the survey of the Federal City or with the final establishment of the boundaries of the Federal District.[2] Nevertheless, in 2016, Charlie Clark, a columnist writing in a Falls Church newspaper, stated that Banneker had placed a district boundary stone in Clark's Arlington County, Virginia, neighborhood.[83]

A 2016 booklet that the government of Arlington County, Virginia, published to promote the County's African American history stated, "On April 15, 1791, officials dedicated the first boundary stone based on Banneker's calculations."[84] However, it was actually a March 30, 1791, presidential proclamation by George Washington that established "Jones's point, the upper cape of Hunting Creek in Virginia" as the starting point for the federal district's boundary survey.[85]

Washington did not need any calculations to determine the location of Jones Point. Further, according to an April 21, 1791, news report of the dedication ceremony for the first boundary stone (the south cornerstone), it was Andrew Ellicott who ″ascertained the precise point from which the first line of the district was to proceed". The news report did not mention Banneker's name.[86]

A National Park Service web page entitled Benjamin Banneker and the Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia stated in 2017:

Along with a team, Banneker identified the boundaries of the capitol city. They installed intermittent stone markers along the perimeter of the District.[87]

The Park Service did not provide a source for this statement.

Banneker's clock

In 1845, John Hazelhurst Boneval Latrobe, an American lawyer, inventor and future president of the American Colonization Society,[88] read a Memoir of Benjamin Banneker at a meeting of the Maryland Historical Society.[89]

Latrobe's memoir, presented 39 years after Banneker's death, contains the first known account of Banneker's clock. The memoir stated:

It was at this time, when he (Banneker) was about thirty years of age, that he contrived and made a clock, which proved an excellent time–piece. He had seen a watch, but not a clock, such an article having not yet having found its way into the quiet and secluded valley in which he lived. The watch was therefore his model.[90]

In 1863, the Atlantic Monthly magazine published during the American Civil War a brief biography of Banneker that an American abolitionist minister, Moncure D. Conway, had written.[91] Embellishing Latrobe's account of Banneker's clock, Conway described the timepiece as follows:

Perhaps the first wonder amongst his comparatively illiterate neighbors was excited, when about the thirtieth year of his age, Benjamin made a clock. It is probable that this was the first clock of which every portion was made in America; it is certain that it was as purely as his own invention as if none had ever been made before. He had seen a watch, but never a clock, such an article not being within fifty miles of him. The watch was his model.[92]

Conway's biography concluded by stating "... history must record that the most original scientific intellect which the South has yet produced was that of the pure African, Benjamin Banneker."[93]

Lydia Maria Child (circa 1865)

In 1865, an American abolitionist, Lydia Maria Child, authored a book intended to be used to teach recently freed African Americans to read and to provide them with inspiration.[94] Child's book stated that Banneker had constructed "the first clock ever made in this country".[95]

Kelly Miller

In 1902, Kelly Miller, a professor of mathematics at Howard University, made a similar undocumented claim in a United States Bureau of Education publication. Miller, who later became a professor of sociology and dean of the school's College of Arts and Sciences,[96] stated in his paper that Banneker had in 1770 "constructed a clock to strike the hours, the first to be made in America".[97] In contrast, Philip Lee Phillips, a Library of Congress librarian,[98] more cautiously stated in a 1916 paper read before the Columbia Historical Society in Washington, D.C., that Banneker "is said to have made, entirely with his own hand, a clock of which it is said every portion was made in America."[99]

In 1919, Carter Woodson wrote in the second edition of his book, The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861, that Banneker had "made in 1770 the first clock manufactured in the United States, thereby attracting the attention of the scientific world".[100] In 1921, Benjamin Griffith Brawley, who had earlier worked at Howard University and had served as the first dean of Morehouse College,[101] authored a book entitled A Social History of the American Negro. Repeating Kelly Miller's claim, Brawley's book stated that Banneker had in 1770 "constructed the first clock striking the hours that was made in America."[102]

In 1929, The Chicago Defender newspaper reported that a speaker at a ceremony dedicating a sundial commemorating Banneker at Howard University had stated that "Banneker made the first clock used in America which was constructed of all American materials".[103] In 1967, William Loren Katz repeated this statement in his book, Eyewitness: The Negro in American History. Katz claimed that Banneker as a teenager had "constructed a clock, the first one made entirely with American parts", a claim that Bedini refuted in 1972.[104]

Shirley Graham wrote in her 1949 book, Your Most Humble Servant, that stories saying that Banneker made the first clock constructed in America are "no doubt carelessly written". She went on to write that it was probably quite safe to say that "Banneker made the first clock in Maryland" or perhaps in the southern Atlantic colonies. Without citing any supporting documents written during Banneker's lifetime, she then claimed that "this at least is what was said about him in his own day".[105]

In 1963, Russell Adams wrote in his book Great Negroes, Past and Present that Banneker's clock was believed to be the first clock wholly made in America and that the clock was the first in America to strike off the hours.[106] In 1968, a writer for the magazine Negro Digest stated that, at the age of 21, Banneker "perfected the first clock in Maryland, possibly in America".[107] In his 1970 book entitled Black History: Lost, Stolen, or Strayed, Otto Lindenmeyer stated that Banneker had constructed his clock's frame and movements "entirely of wood, the first such instrument made in America".[108]

In a book entitled Black Pioneers of Science and Invention that was also published in 1970, Louis Haber wrote that Banneker had by 1753 completed "the first clock ever built in the United States", that the device kept perfect time for more than 40 years, and that "People came from all over the country to see his clock."[109] The preface to Haber's book reported that his work had resulted in part from a United States Office of Education grant to "gather resource materials that could then be incorporated into science curricula at elementary and secondary schools as well as at the college level".[110]

In 1976, an Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation historian prepared a National Register of Historic Places nomination form for a District of Columbia boundary marker stone whose proposed name would commemorate Banneker. The form's "Statement of Significance" claimed that Banneker was an inventor whose "ability as a mathematician enabled him to construct what is believed to have been the first working wooden clock in America".[111] In 1978, the Baltimore Afro-American reported that Banneker was the "inventor of the first clock".[112]

In 1980, the United States Postal Service (USPS) issued a postage stamp that commemorated Banneker. A USPS description of Banneker stated: "... In 1753, he built the first watch made in America, a wooden pocket watch."[113]

In 1987, Oregon's Portland Public Schools District published a series of educational materials entitled African-American Baseline Essays. The Essays were to be "used by teachers and other District staff as a reference and resource just as adopted textbooks and other resources are used" as part of "a huge multicultural curriculum-development effort."[114] An Essay entitled African-American Contributions to Science and Technology stated that Banneker had "made America's first clock".[115]

In 1994, Erich Martel, who had earlier authored a 1991 paper describing the Essays' deficiencies,[116] wrote an article for the Washington Post that cited the Essays' "crippling flaws" while noting that the Essays "are the most widespread Afrocentric teaching material".[117] The specified flaws included several Banneker stories that Silvio Bedini had refuted more than a decade before the Essays appeared.[117]

In his 1998 book, A Country of Strangers: Blacks and Whites in America, David Shipler wrote in a section entitled "Myths of America" that the Essays had "been attacked for gross inaccuracy in an entire literature of detailed criticism by respected historians". Shipler noted that the science section of the Essays had embellished Banneker's accomplishments in several ways, one of which was the demonstrably false claim that Banneker's clock was America's first such instrument.[3]

Nevertheless, Benjamin Banneker: Invented America's First Clock became the title of a 2008 web page.[118] In 2014, a revised edition of a 1994 book entitled African-American Firsts repeated a statement made in the initial edition that claimed that Banneker had "designed and built the first clock in the colonies".[119] Similarly, the author of a 2014 web page describing the early history of the Banneker Elementary School in Saint Louis, Virginia, stated that Banneker had in 1753 constructed the first clock made entirely in America.[120]

In 1999, the author of an article entitled A Salute to African American Inventors that a Fort Smith, Arkansas, newspaper published wrote that in 1753, Banneker "built one of the first watches made in America, a wooden pocket watch".[121] The article did not provide a source for this statement, which was similar to the one that the USPS had made in 1980.[113] A 2020 update of an on-line biography of Banneker contained an identical statement while also not citing the statement's source.[122] The author of a 2013 book entitled Famous Americans: A Directory of Museums, Historic Sites, and Memorials wrote that Banneker "became known for such accomplishments as building one of the first watches in America".[123]

A 2004 USPS pamphlet illustrating the 1980 Banneker postage stamp stated that Banneker had "constructed the first wooden striking clock made in America",[124] a statement which also appeared on a web page of the Smithsonian Institution's National Postal Museum entitled "Early Pioneers".[125] The website of the Banneker-Douglass Museum, the State of Maryland's official museum of African American heritage, similarly claimed in 2015 that Banneker crafted "the first wooden striking clock in America".[126]

When supporting the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African American History and Culture, a 2004 report to the President of the United States and the United States Congress stated that Banneker was an African American inventor.[127] In 2015, columnists Al Kamen and Colby Itkowitz repeated that statement in a Washington Post article.[128] A 2017 National Park Service web page, which also claimed that Banneker was an inventor, stated that Banneker had "constructed one of the first entirely wooden clocks in America."[29]

However, while several 19th, 20th and 21st century biographers have written that Banneker constructed a clock, none cited documents that showed that Banneker had not seen or read about clocks before he constructed his own. None showed that Banneker's clock had any characteristics that earlier American clocks had lacked.[99][129]

Sources describing the history of clockmaking in America state that clockmakers came to the American colonies from England and Holland during the early 1600s (see: History of timekeeping devices). Among the earliest known clockmakers in the colonies were Thomas Nash of New Haven, Connecticut (1638),[130] William Davis of Boston (1683), Edvardus Bogardus of New York City (1698) and James Batterson of Boston (1707).[131] Benjamin Chandlee, a clockmaker who had apprenticed in Philadelphia, moved his family in 1712 to Nottingham, Maryland, 19 miles (31 km) from Banneker's future home.[132]

Silvio Bedini reported in 1972 that a number of watch and clockmakers were already established in Maryland before Banneker completed his clock around 1753. Prior to 1750, at least four such craftsmen were working in Annapolis, 25 miles (40 km) from Banneker's home.[133] The only accounts of Banneker's clock by people who had observed it reported only that it was made of wood, that it was suspended in a corner of his log cabin, that it had struck the hour and that Banneker had said that its only model was a borrowed watch.[134]

(2017)

Bedini stated that "Banneker's clock continued to operate until his death".[135] However, a later author more cautiously wrote that the clock "was apparently used" until a fire destroyed Banneker's home during his 1806 funeral.[132] The first known report of the fire, published in 1854 from notes taken in 1836, stated that flames had consumed the clock, but provided no supporting documentation or any information as to whether the clock was still operational at the time.[136]

Banneker's clock was not the first of its kind made in America. Connecticut clockmakers were crafting striking clocks throughout the 1600s, before Banneker was born.[130] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City holds in its collections a tall-case striking clock that Benjamin Bagnall, Sr., constructed in Boston before 1740 (when Banneker was 9 years old) and that Elisha Williams probably acquired between 1725 and 1739 while he was rector of Yale College.[137] The Dallas Museum of Art holds in its collections a similar striking clock made entirely of American parts that Bagnall constructed in Boston between 1730 and 1745.[138]

During the 1600s, when metal was harder to come by in the colonies than wood, works for many American clocks were made of wood, including the gears, which were whittled and fashioned by hand, as were all other parts.[139] There is some evidence that wooden clocks were being made as early as 1715 near New Haven, Connecticut.[130][140]

Benjamin Cheney of East Hartford, Connecticut, was producing wooden striking clocks by 1745,[130][140][141][142] eight years before Banneker completed his own wooden striking clock around 1753. David Rittenhouse constructed a clock with wooden gears around 1749 while living on a farm near Philadelphia at the age of 17.[143]

Banneker's almanacs

In addition to incorrectly describing Banneker's clock, Lydia Maria Child's 1865 book stated that Banneker's almanac was the first ever made in America.[144] After also incorrectly describing the clock, Kelly Miller's 1902 publication similarly stated that Banneker's 1792 almanac for Pennsylvania, Virginia and Maryland was "the first almanac constructed in America".[97] Carter Woodson made a similar statement in his 1919 book, The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861.[145]

A National Register of Historic Places nomination form for the ″Benjamin Banneker: SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone (milestone) of the District of Columbia" that an Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation historian prepared in 1976 states that Banneker's astronomical calculations "led to his writing one of the first series of almanacs printed in the United States."[146] A National Park Service web page repeated that statement in 2017.[29]

However, William Pierce's 1639 An Almanac Calculated for New England, which was the first in an annual series of almanacs that Stephen Daye, or Day, printed until 1649 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, preceded Banneker's birth by nearly a century.[147] Nathaniel Ames issued his popular Astronomical Diary and Almanack in Massachusetts in 1725 and annually after c.1732.[148] James Franklin published The Rhode Island Almanack by "Poor Robin" for each year from 1728 to 1735.[149] James' brother, Benjamin Franklin, published his annual Poor Richard's Almanack in Philadelphia from 1732 to 1758, more than thirty years before Banneker wrote his own first almanac in 1791.[150]

Samuel Stearns issued the North-American Almanack, published annually from 1771 to 1784, as well as the first American nautical almanac, The Navigator's Kalendar, or Nautical Almanack, for 1783.[151] A decade before printers published Banneker's first almanac, Andrew Ellicott began to author a series of almanacs, The United States Almanack, the earliest known copy of which bears the date of 1782.[152]

In 1907, the Library of Congress compiled a Preliminary Check List of American Almanacs: 1639–1800, which identified a large number of almanacs that had been printed in the thirteen colonies and the United States prior to 1792.[153] The printers had published many of these almanacs during more than one year.

The Check List showed that 18 of the almanacs had been printed in Maryland, including Ellicott's Maryland and Virginia Almanack for 1787 and 1789 and Ellicott's Maryland and Virginia almanac and ephemeris for 1791, each of which John Hayes of Baltimore had printed.[154] William Goddard of Baltimore, who later printed Banneker's 1792 almanac, had printed The Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanack and ephemeris for each year from 1784 to 1790, except 1786.[154]

Plan of a Peace-Office

A Philadelphia edition of Banneker's 1793 almanac contained an anonymous essay entitled "A Plan of a Peace-Office, for the United States".[155][156] wrote a paper about the almanac that was presented to the Columbia Historical Society in Washington, D.C. Phillips' paper, which stated that the almanac contained Banneker's plea for peace, also contained a complete copy of the essay.[157]

A report of the presentation that the Washington Star published soon afterwards stated that, in the course of the paper, "it was brought out that Banneker, who was a free Negro, friend of Washington and Jefferson, published a series of almanacs, unique in that they were his own work throughout."[158] A number of books, journals, newspapers and student teaching aids then credited Banneker with the authorship of the peace plan during the more than 100 years that passed after Phillips' paper and the Star's report were published.[159][160]

However, in 1798, a Philadelphia printer had earlier published a collection of essays that Dr. Benjamim Rush, a signer of the 1776 Declaration of Independence, had written.[161] Rush's preface to the publication, dated January 9, 1798, stated that most of the essays had been published soon after the end of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783).[162]

One of Rush's essays, entitled A plan of a Peace-Office for the United States was similar, but not identical, to the essay with the same name in Banneker's 1793 almanac.[163] Several historians have therefore attributed to Dr. Rush the authorship of the almanac's peace plan.

Henry Cadbury, a historian serving as a professor of divinity at Harvard University from 1934 to 1954,[164] discovered within Rush's papers a copy of the peace plan that bore a date that was earlier than the publication of Banneker's 1793 almanac.[165] In 1946, Dagobert D. Runes published a collection of Rush's papers that contained the 1798 peace plan, but which Runes dated as 1799.[165][166]

After Runes' collection was published, Carter Woodson, who had in his 1933 book, The Mis-Education of the Negro, credited Banneker with being the author of the peace plan,[159] noted that the copy of the plan in Banneker's almanac contained Rush's initials ("B.R."). Woodson concluded that Phillips had been misled because the initials were not clear. Woodson further concluded that Banneker could not be regarded as the author of the plan.[165]

However, Shirley Graham's 1949 book, Your Most Humble Servant, presented a contrasting view. Graham noted that the editors of Banneker's almanac had placed the peace plan in their work. Stating that Runes' collection contained the first printing of Dr. Rush's peace plan, Graham claimed that Rush had revised the almanac's plan because it was "too fanciful".[167]

Graham stated in the book's section on sources that the peace plan in a photographed copy of Banneker's 1793 almanac did not contain any initials.[168] However, consistent with Woodson's account, two digitized copies of a Philadelphia edition of that almanac show beneath the last page of the peace plan the letter "B", but do not show any other letters.[169]

In a typed draft of an unpublished article that he wrote around 1950, historian and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois concurred with Graham, whom he later married. His article stated that Graham's book indicated the facts and that "Banneker first published the plan and without much doubt was its author". The article concluded that "The credit of this remarkable suggestion should go to Benjamin Banneker".[170]

In 1969, Maxwell Whiteman authored a book that contained a reproduction of the almanac. Whiteman wrote in the book's introduction that the librarian of the Library Company of Philadelphia, from whose institution the copy had been made, had stated that Dr. Rush had authored the peace plan that the almanac contained.[171] Silvio Bedini wrote in his 1972 biography of Banneker that Runes' 1947 collection of Rush's writings had "identified beyond question" that Rush had authored the almanac's peace plan.[172]

Astronomical works

In 2019, a Harvard University website describing a program that the "Banneker Institute" conducted at the school each summer claimed about Banneker: "As a forefather to Black American contributions to science, his eminence has earned him the distinction of being the first professional astronomer in America."[173] The website, which noted that the program "prepares undergraduate students of color for graduate programs in astronomy by emphasizing research, building community, and encouraging debate and political action through social justice education",[174] did not cite the source of this questionable information, which at least one writer has reported to be incorrect.[175]

Banneker prepared his first published almanac in 1791, during the same year that he participated in the federal district boundary survey.[176][177] As a 1942 journal article entitled Early American Astronomy has reported, American almanacs published as early as 1687 predicted eclipses and other astronomical events. In contrast to the statement in the Banneker Institute's posting, that article and others that have reported the works of 17th and 18th century American astronomers either do not mention Banneker's name or describe his works as occurring after those of other Americans.[178][179]

Colonial Americans John Winthrop (a Harvard College professor) and David Rittenhouse authored publications that described their telescopic observations of the 1761 and 1769 transits of Venus soon after those events occurred.[180] Other Americans, some of whom taught at Harvard, also wrote about astronomy and used telescopes when observing celestial bodies and events before 1790 (see also: Colonial American Astronomy).[178]

A book relating the history of American astronomy stated, that as a result of the American Revolution, "... what astronomical activity there was from 1776 through 1830 was sporadic and inconsequential".[181] Another such book has stated that "the dawn of American professional astronomy" began in the middle of the 19th century.[182] In 1839, the Harvard Corporation voted to appoint clockmaker William Cranch Bond, whom some consider to be the "father of American astronomy", as "Astronomical Observer to the University".[182][183]

Seventeen-year cicada

(June 2004)

In 2004, during a year in which Brood X of the seventeen-year periodical cicada (Magicicada septendecim and related species or seventeen-year "locust") emerged from the ground in large numbers, columnist Courtland Milloy wrote in The Washington Post an article entitled Time to Create Some Buzz for Banneker.[184] Milloy claimed that Banneker "is believed to have been the first person to document this noisy recurrence" of the insect.[184] At least one writer has stated that such claims are incorrect.[185]

Milloy stated that Banneker had recorded in a journal "published around 1800" that the "locusts" had appeared in 1749, 1766 and 1783.[184] He further noted that Banneker had predicted that the insects would return in 1800.[184][186]

In 2014, the authors of a publication that reproduced Banneker's handwritten journal report cited Milloy's article.[187] The writers contended within their work that "Banneker was one of the first naturalists to record scientific information and observations of the seventeen-year cicada".[187]

Earlier published accounts of the periodical cicada's life cycle describe the history of cicada sightings differently. These accounts cite descriptions of fifteen- to seventeen-year recurrences of enormous numbers of noisy emergent cicadas that people had written as early as 1733,[188][189] when Banneker was two years old. John Bartram, a noted Philadelphia botanist and horticulturist, was among the early writers who described the insect's life cycle, appearance and characteristics.[190]

Pehr Kalm, a Finnish naturalist visiting Pennsylvania and New Jersey in 1749 on behalf of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, observed in late May the first of the three Brood X emergences that Banneker's journal later documented.[188][191][192] When reporting the event in a paper that a Swedish academic journal published in 1756, Kalm wrote:

The general opinion is that these insects appear in these fantastic numbers in every seventeenth year. Meanwhile, except for an occasional one which may appear in the summer, they remain underground.

There is considerable evidence that these insects appear every seventeenth year in Pennsylvania.[192]

Kalm then described documents (including one that he had obtained from Benjamin Franklin) that had recorded in Pennsylvania the emergence from the ground of large numbers of cicadas during May 1715 and May 1732. He noted that the people who had prepared these documents had made no such reports in other years.[192]

Kalm further noted that others had informed him that they had seen cicadas only occasionally before the insects appeared in large swarms during 1749.[192] He additionally stated that he had not heard any cicadas in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in 1750 in the same months and areas in which he had heard many in 1749.[192] The 1715 and 1732 reports, when coupled with his own 1749 and 1750 observations, supported the previous "general opinion" that he had cited.

Kalm summarized his findings in a book translated into English and published in London in 1771,[193] stating:

There are a kind of Locusts which about every seventeen years come hither in incredible numbers ... In the interval between the years when they are so numerous, they are only seen or heard single in the woods.[188][194]

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus gave to the insect that Kalm had described the Latin name of Cicada septendecim (seventeen-year cicada) in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[195] Banneker's second observation of a Brood X emergence occurred eight years later. Moses Bartram, a son of John Bartram, documented that emergence in a 1766 article entitled Observations on the cicada, or locust of America, which appears periodically once in 16 or 17 years that a London journal published in 1768.[196]

Other legends and embellishments

In her 1865 work, The Freedmen's Book, Lydia Maria Child stated that Thomas Jefferson had in 1803 invited Banneker to visit him in Monticello, a claim that Carter Woodson repeated in his 1919 book,The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861.[197] Silvio Bedini later reported that Child had not substantiated this claim.[198]

Bedini noted that a writer had repeated this statement in 1876 within a Scottish book entitled Amongst the Darkies [199] and that another writer had in 1916 not only repeated the claim but had also stated that Jefferson invited Banneker to dine with him at the Executive Mansion (the White House).[200] Bedini further noted that these legends contain dates that are inconsistent with those that are known[201] and that no evidence of any such invitations has been found.[202]

In 1930, writer Lloyd Morris claimed in an academic journal article entitled The Negro "Renaissance" that "Benjamin Banneker attracted the attention of a President... President Thomas Jefferson sent a copy of one of Banneker's almanacs to his friend, the French philosopher Condorcet...".[203] However, Thomas Jefferson sent Banneker's almanac to the Marquis de Condorcet in 1791, a decade before he became president in 1801.[204][205]

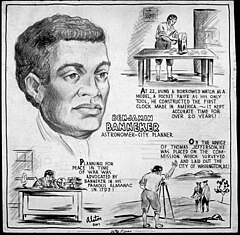

Charles Alston (1939)

In 1943, an African American artist, Charles Alston, who was at the time an employee of the United States Office of War Information, designed a cartoon that embellished the statements that Henry E. Baker had made in 1918.[57] Like Baker, Alston incorrectly claimed that Banneker "was placed on the commission which surveyed and laid out the city of Washington, D.C." Alston extended this claim by also stating that Banneker had been a "city planner". Alston's cartoon additionally repeated a claim that Lydia Maria Child had made in 1865[95] by stating that Banneker had "constructed the first clock made in America".[206]

In 1976, the singer-songwriter Stevie Wonder celebrated Banneker's mythical feats in his song "Black Man", from the album Songs in the Key of Life. The lyrics of the song state:

Who was the man who helped design the nation's capitol,

Made the first clock to give time in America and wrote the first almanac?

Benjamin Banneker, a black man[207]

The question's answer is incorrect. Banneker did not help design either the United States Capitol or the nation's capital city and did not write America's first almanac.[34] The first known clockmaker of record in America was Thomas Nash, an early settler of New Haven, Connecticut, in 1638.[130]

In 1998, a Catalan writer, Núria Perpinyà, created a fictional character, Aleph Banneker, in her novel Un bon error (A Good Mistake). The writer's website reported that the character, an "eminent scientist", was meant to recall Benjamin Banneker, an eighteenth-century "black astronomer and urbanist".[208] However, none of Banneker's documented activities or writings suggest that he was an "urbanist".[14]

In 1999, the National Capital Memorial Commission concluded that the relationship between Banneker and L'Enfant was such that L'Enfant Promenade was the most logical place in Washington, D.C., on which to construct a proposed memorial to Banneker.[209] However, Silvio Bedini was not able find any historical evidence that showed that Banneker had any relationship at all to L'Enfant or to L'Enfant's plan for the city, although he wrote that the two men had "undoubtedly" met each other after L'Enfant arrived in Georgetown in March 1791 to begin his work.[210][211] A 2016 National Park Service (NPS) publication later stated that the NPS had renamed an overlook at the southern end of the Promenade to commemorate Banneker even though the area had no specific connection to Banneker himself.[212]

A history painting by Peter Waddell entitled A Vision Unfolds debuted in 2005 within an exhibition on Freemasonry that the Octagon House's museum in Washington, D.C., was hosting. The oil painting was again displayed in 2007, 2009, 2010 and 2011, first in the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, and later in the National Heritage Museum in Lexington, Massachusetts, and in the Scottish Rite Center of the District of Columbia in Washington, D.C.[213] Waddell's painting contains elements present in Edward Savage's 1789–1796 painting The Washington Family, which portrays President George Washington and his wife Martha viewing a plan of the City of Washington.[214]

A Vision Unfolds depicts a meeting that is taking place within an elaborate surveying tent. In the imaginary scene, Banneker presents a map of the federal district (the Territory of Columbia) to President Washington and Andrew Ellicott.[213][215]

However, Andrew Ellicott completed his survey of the federal district's boundaries in 1792.[32][70] On January 1, 1793, Ellicott submitted to the three commissioners "a report of his first map of the four lines of experiment, showing a half mile on each side, including the district of territory, with a survey of the different waters within the territory".[216]

The Library of Congress has attributed to 1793 the year of Ellicott's earliest map of the Territory of Columbia that the library holds within its collections.[215] As Banneker left the federal capital area in 1791,[2][217][14] Banneker could not have had any association with the map that Waddell depicted.

Further, writers have pointed out that there is no evidence that Banneker had anything to do with the final establishment of the federal district's boundaries.[2] Additionally, a researcher has been unable to find any documentation that shows that President Washington and Banneker ever met.[69]

A 2017 article on the Smithsonian Magazine's website entitled Three Things to Know About Benjamin Banneker's Pioneering Career stated that the first two of these three things were "He built America's first home-grown clock–out of wood" and "He produced one of the United States' first almanacs."[218] However, a wooden clock that David Rittenhouse constructed around 1749[143] was among those made at home in the thirteen American colonies before Banneker built his own around 1753.[135] A report that the Library of Congress published in 1907 identified many almanacs that printers had distributed in the thirteen colonies and the United States between William Pierce's 1639 Cambridge, Massachusetts, publication and Banneker's first (Baltimore, Maryland, 1792).[219]

In 2018, an NPS web page stated that "Banneker became one of the first black civil servants of the new nation" when "he surveyed the city of Washington".[29] However, Bedini had reported more than 40 years earlier that it was Andrew Ellicott (not the federal government) who hired Banneker to participate in the survey of the federal district.[32] Ellicott advanced Banneker $60 for travel expenses to and at Georgetown, where planning for the survey began.[11]

A 2019 article on the White House Historical Association's website entitled Benjamin Banneker: The Black Tobacco Farmer Who The Presidents Couldn't Ignore stated that President Washington was aware of Banneker's participation in the federal city's boundary survey. However, the article neither cited a source for this claim nor referenced a contemporary document that supported the statement.[220]

The article's reference list cited a 2002 book whose author had claimed that "President Washington must have been thunderstruck by finding an African-American on the (survey) team"[221] and that "there is evidence" that a newspaper reporter "asked the President about Banneker on one of his visits to the survey site".[221] However, a reviewer of that book stated that such statements lacked direct documentation and ended the review by stating that the author's "documentation is sloppy".[222]

Commemorative U.S. quarter dollar coin nomination

In 2008, the District of Columbia government considered selecting an image of Banneker for the reverse side of the District of Columbia quarter in the 2009 District of Columbia and United States Territories quarters program.[223] The original narrative supporting this selection (subsequently revised)[224] alleged that Banneker was an inventor, "a noted clock-maker", "was hired as part of an official six-man team to help survey and design the new capital city of the fledgling nation, making Benjamin Banneker among the first-ever African-American presidential appointees" and that Banneker was "a founder of Washington D.C."[225] When describing the finalists for the image, the Fiscal Year 2008 annual report of the Secretariat of the District of Columbia stated that Banneker "helped Pierre L'Enfant create the plan for the capital city".[226]

After the District chose to commemorate another person on the coin, the District's mayor, Adrian M. Fenty, sent a letter to the director of the United States Mint, Edmund C. Moy, that claimed that Banneker "played an integral role in the physical design of the nation's capital."[227] However, there are no known documents that show that any president ever appointed Banneker to any position, that Banneker ever invented anything, or that Banneker was a "noted clock-maker". Further, Julian P. Boyd had written in 1974 that Banneker had played no role at all in the design, development or founding of the nation's capital beyond his brief participation in the two-year survey of the federal district's boundaries.[2]

Historical markers

Several historical markers in Maryland and Washington, D.C., contain information relating to Benjamin Banneker that is unsupported by historical evidence or is contradicted by such evidence:

Historical marker in Benjamin Banneker Historical Park, Baltimore County, Maryland

A commemorative historical marker that the Maryland Historical Society erected on the present grounds of Benjamin Banneker Historical Park in Baltimore County, Maryland, states that Banneker "published the first Maryland almanac" in 1792.[228] However, an Annapolis printer published for the year of 1730 the first of many known almanacs whose titles contained the name of Maryland.[229] More than 50 of these had appeared before Banneker's first almanac did.[230]

Silvio Bedini reported in 1999 that the marker's statement is incorrect.[11] Bedini stated that Banneker may have modeled the format of his almanac after a series of Maryland almanacs that Andrew Ellicott had authored from 1781 to 1787.[231]

Further, Banneker did not "publish" his 1792 almanac. Although he authored this work, others printed, distributed and sold it.[176]

Historical marker in Benjamin Banneker Park, Washington, D.C.

A historical marker that the National Park Service erected in Benjamin Banneker Park in Washington, D.C., in 1997[232][a 1] states in an unreferenced paragraph:

Banneker became intrigued by a pocket watch he had seen as a young man. Using a knife he intricately carved out the wheels and gears of a wooden timepiece. The remarkable clock he constructed from memory kept time and struck the hours for the next fifty years.[233]

However, Banneker reportedly completed his clock around 1753 at around the age of 21, when he was still a young man.[234] No historical evidence shows that he constructed the clock from memory.[235]

Further, it is open to question as to whether the clock was actually "remarkable". Silvio Bedini reported that at least four clockmakers were working in Annapolis, Maryland, before 1753, when Banneker completed his own clock.[133]

A photograph on the historical marker illustrates a wooden striking clock that Benjamin Cheney constructed around 1760.[233][236] The marker does not indicate that the clock is not Banneker's.[233] A fire on the day of Banneker's funeral reportedly destroyed his own clock.[132][136]

Historical marker in Newseum, Washington, D.C.

In 2008, when the Newseum opened to the public on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., visitors looking over the avenue could read a historical marker that stated:

Benjamin Banneker assisted Chief Surveyor Andrew Ellicott in laying out the Avenue based on Pierre L'Enfant's Plan. President George Washington appointed Ellicott and Banneker to survey the boundaries of the new city.[237]

Little or none of this appears to be correct. Banneker had no documented involvement with the laying out of Pennsylvania Avenue or with L'Enfant's Plan.[2][217][34] Andrew Ellicott surveyed the boundaries of the federal district (not the "boundaries of the new city") at the suggestion of Thomas Jefferson.[65] Ellicott (not Washington) appointed Banneker to assist in the boundary survey.[32][11]

List and map of coordinates

Download coordinates as:

- KML

- GPX (all coordinates)

- GPX (primary coordinates)

- GPX (secondary coordinates)